Namibian Finance Minister Calle Schlettwein lost his temper over numbers and letters that were meant to evaluate his country’s credit risks.

The rating was “confusing” and “puzzling,” he said in the summer of 2017 after he learned Namibia had been downgraded from “Baa3” to “Ba1” by US ratings agency Moody’s — turning Namibian state bonds into “speculative” risks with “substantial credit risk.”

Still, Namibia has it better than most African countries: Fourteen out of 21 rated African states have been given even lower ratings such as “high credit risk” or “very high credit risk” by Moody’s.

These ratings have irked many African governments. Three US ratings agencies dominate the global market: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch.

“That is part of the criticism, that it isn’t a very robust analytical process, there is a high degree of subjectivity to it,” said Sean Gossel, who teaches economics at the University of Cape Town.

“Much of the criticism is that the personnel making these ratings do not understand the African environment and do not understand the challenges that African countries in particular face,” Gossel told DW.

Criticism not only voiced in Africa

A lot hinges on the cryptic combination of numbers and letters. A bad rating tells investors to look elsewhere if they are interested in secure investments. “Central banks and many public pension funds have clear instructions in which asset categories they are allowed to invest,” said Kai Gehring, senior economics researcher at the University of Zurich.

Some countries miss out on potential investments that are worth millions. Those with bad ratings also have to pay higher interest rates when borrowing money from international financial markets.

It’s not just Africa that’s been criticizing ratings agencies. European experts said ratings agencies downgraded Greek state bonds far too quickly during the euro crisis which in turn had worsened the situation.

Even Wolfgang Schäuble, who was Germany’s finance minister back then, said: “We need to break the ratings agencies’ oligopoly.”

How objective are ratings agencies?

But are ratings by ratings agencies biased? Moody’s told DW in writing that it’s never just one analyst alone who decides on a country’s rating; ratings are compiled by a committee to incorporate a broad range of expertise.

The agencies look at a number of factors: Is a country politically stable or on the brink of civil war? Has the respective government always paid back its debts on time? Does the country have independent courts so an investor could sue over outstanding debts?

About 80 percent of all ratings can be explained by these factors, said Gehring. He and a colleague examined the agencies’ ratings methods and found the remaining 20 percent can be traced back to subjective factors.

“You have to understand that part of it is also an assessment of the future. You don’t just look at past data points, but you also try to project that into the future,” Gehring told DW. That means differences in culture or language between the country where the ratings agency is based or where the analysts are from and the country that’s being rated do indeed play a role, he added.

An African nation could easily be classified one category lower than a comparable European country due to these subjective factors, Gehring found out.

African economists are demanding agencies should be more strictly regulated to avoid that.

“African countries should design a collective response mechanism to save the continent from rating abuse,” wrote Misheck Mutize, a South African lecturer in finance with the University of Cape Town. He suggests the African Union establish a regulatory authority for ratings agencies and put in place a standard framework and assess whether ratings are fair.

How about an African ratings agency?

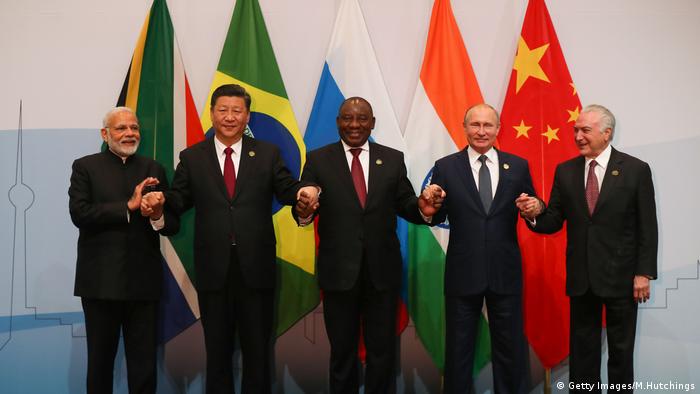

The South African government — which has also been downgraded by several ratings agencies — even goes a step further. South Africa plans to come up with its own rating agency with the help of other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China). But it’s unclear whether international investors would trust such an agency.

Gossel has another idea. He believes ratings would turn out differently if ratings agencies became more familiar with the African context. “The ratings agencies need to be much more involved on a domestic level. It is not just enough to fly in occasionally, gather data and then leave,” he told DW.

The website of market leader Standard & Poor’s, for instance, says the agency evaluates 128 countries. But there’s only one office on the African continent — in South Africa’s economic capital Johannesburg.

Even though Zurich-based economist Gehring would also favor a stronger local presence by ratings agencies, he doesn’t believe it would fundamentally change the outcome.

“A large part of ratings can be explained by economic and political factors. That’s often risk of conflict or credit history in Africa,” he said. That puts the ball back into the court of African governments and their political decisions.

Source: DW/ Daniel Pelz